A-1 Skyraider Wreck Dive Media

HIDDEN IN PLANE SIGHT!

KOREAN ERA A-1 SKYRAIDER WRECKAGE DISCOVERED OFF SAN DIEGO COAST.

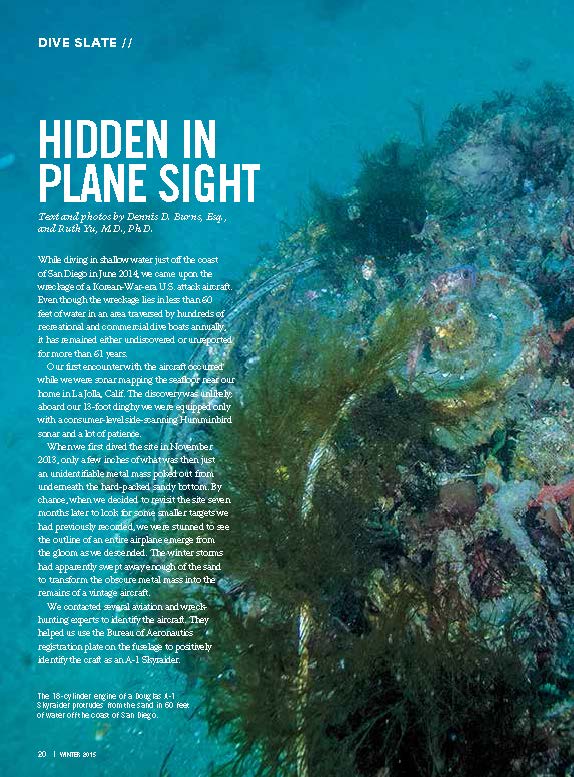

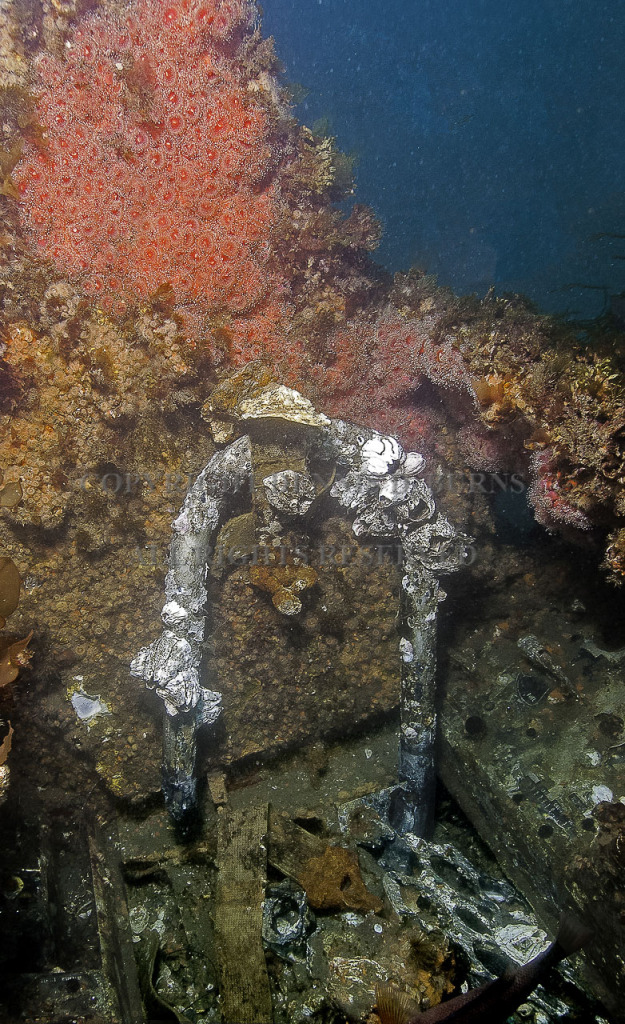

In June 2014, my dive buddy and I discovered the wreckage of a Korean War era attack bomber aircraft in shallow water just off the coast of San Diego. The wreckage lies in less than 60 fsw, in an area frequently traversed by hundreds of recreational and commercial dive boats annually. The aircraft’s remains have apparently been undiscovered or unreported for over 61 years.

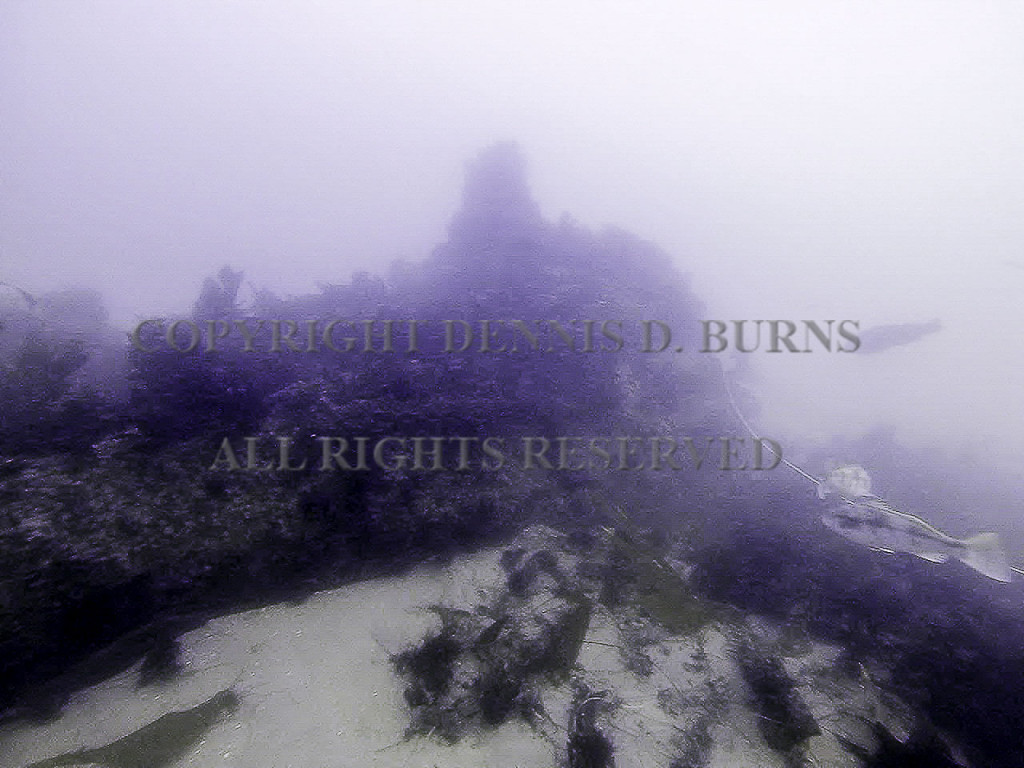

On our initial dive at the site in November 2013, only a few inches of an unidentifiable metal mass was visible above a hard-packed sandy bottom. By chance, eight months later in June of 2014, we revisited the site looking for smaller targets that we had previously recorded. On this second dive, we were stunned to see the outline of an airplane emerge from the gloom as we descended. Apparently winter storms had transformed the metal mass into the remains of a vintage aircraft.

(Above, right to left, Fuselage from Starboard side, Inverter and Interior Lighting Switches, Twin Cannons on Port Wing, Curtiss-Wright Cyclone 3350 Engine Nose Down in Sand, 20mm Cannon Bore, Cockpit Gauge Cluster Bezel.)

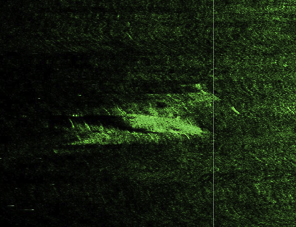

We found the wreckage while sonar mapping the sea bottom near our home in La Jolla, California on our 13-foot dinghy “Zig Zag” utilizing only a Humminbird consumer level side scanning sonar and a lot of patience.

At first we questioned whether the aircraft was authentic or a mock-up for use as some form of naval training exercise left abandoned by the Navy. As we inspected the remains more thoroughly, however, it became clear that this was indeed an aviation wreck site. Still, its

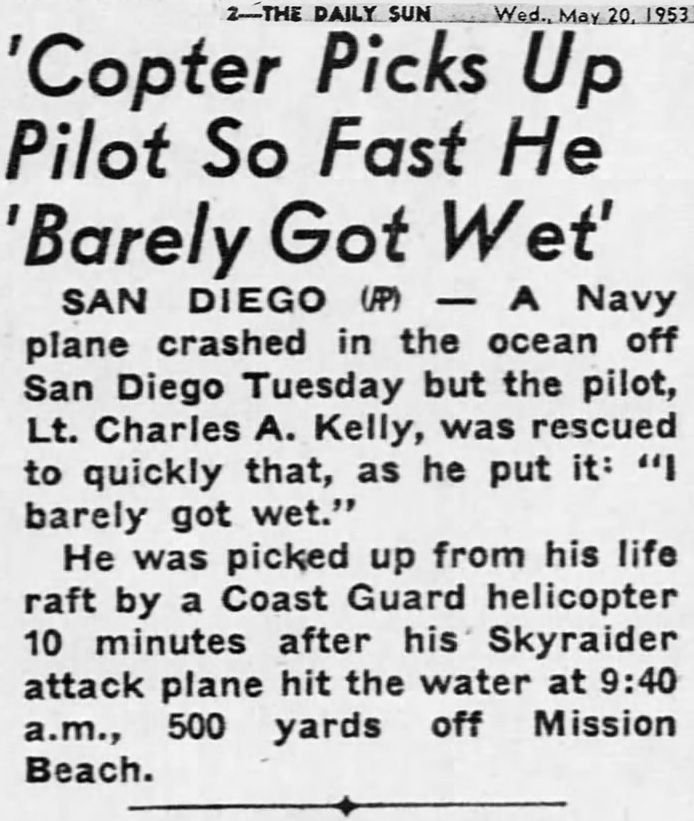

easily accessible location gave us some pause. Could it be that we were simply unaware of this dive site? We have been diving extensively in San Diego for 45 years and never heard reference to any airplane wreck dive site south of Del Mar. We inquired of local senior divers Chuck Nicklin, Bob Gladden and Joe Barnett, all of whom confessed they had no knowledge of a military plane wreck site in the area we described. The condition of the wreck, rich with artifacts, also added credence to our belief that the warbird had been left untouched since its demise in 1953. We found no public records referencing the crash with the sole exception of a lone newspaper article published in 1953. Even the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration had no listing of this crash site on its maritime wreck and obstructions register.

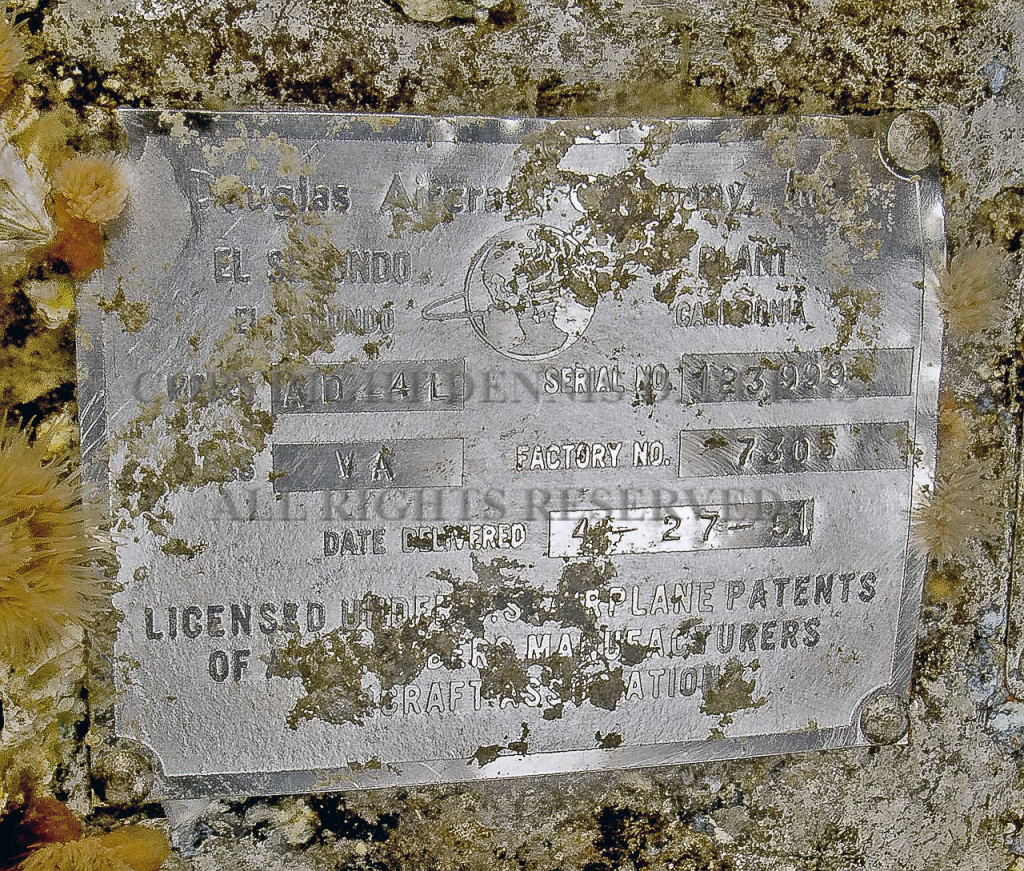

(Above Photographs Showing Serial Number of Aircraft on BuPlate and on Tail of Aircraft Aboard Carrier U.S.S. Antietam on its way to Korea in 1951.)

In order to identify the aircraft, we contacted several aviation and wreck hunting experts. Positive identification of the craft as an A-1 Skyraider was achieved by locating the Bureau of Aeronautics registration plate on the fuselage. The information from the plate allowed us to access naval records that revealed the plane’s production in 1951, its Korean conflict service history and ultimate demise on May 19th 1953. Surprisingly, we also found a photograph of the aircraft during its assignment to the aircraft carrier U.S.S. Antietam.

According to the official incident report, the warbird was ditched by its pilot after engine trouble while on a training exercise in May 1953. The pilot landed the airplane in one piece on the ocean’s surface, exited the craft without incident and was rescued by a helicopter. The plane reportedly sank less than one minute after landing. A twelve day, unsuccessful salvage operation by the Navy was attempted on the aircraft just days after the crash.

Unfortunately, the pilot, Reserve Officer Lt. Charles A. Kelly, is no longer with us. Having passed away on June 13, 1999. (Click on his name above for information on his career and family.)

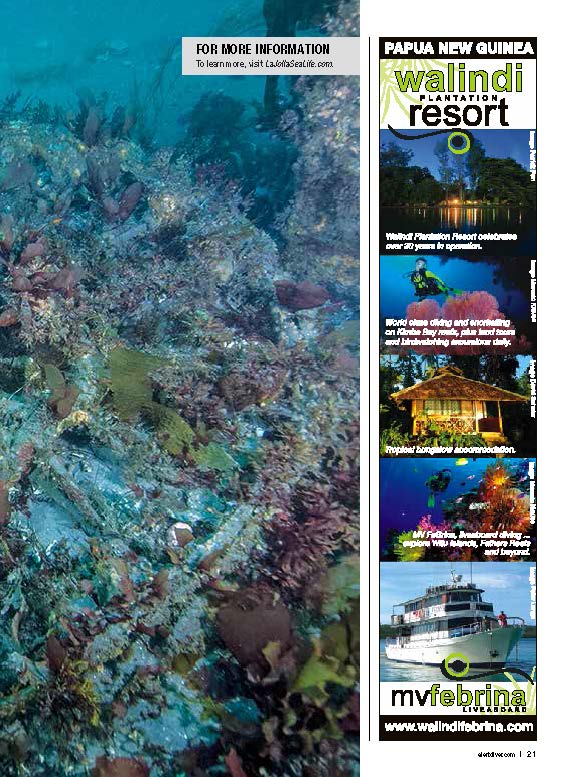

The site changes on a weekly basis with sand being pulled away one week and being re-deposited the next. New areas of the wreck are exposed and then completely buried a short time later.

The visibility at the site, due to its shallow depth, sandy bottom and proximity to the shore, is typically poor making wide angle photography difficult.

Methods used to Identify and Verify the Site Wreckage

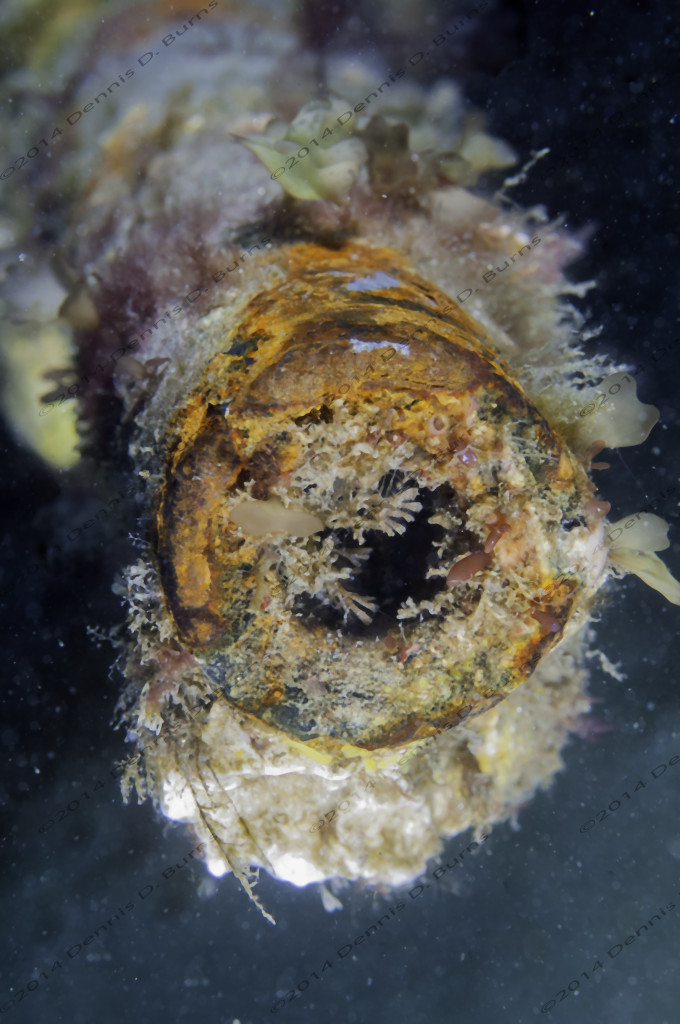

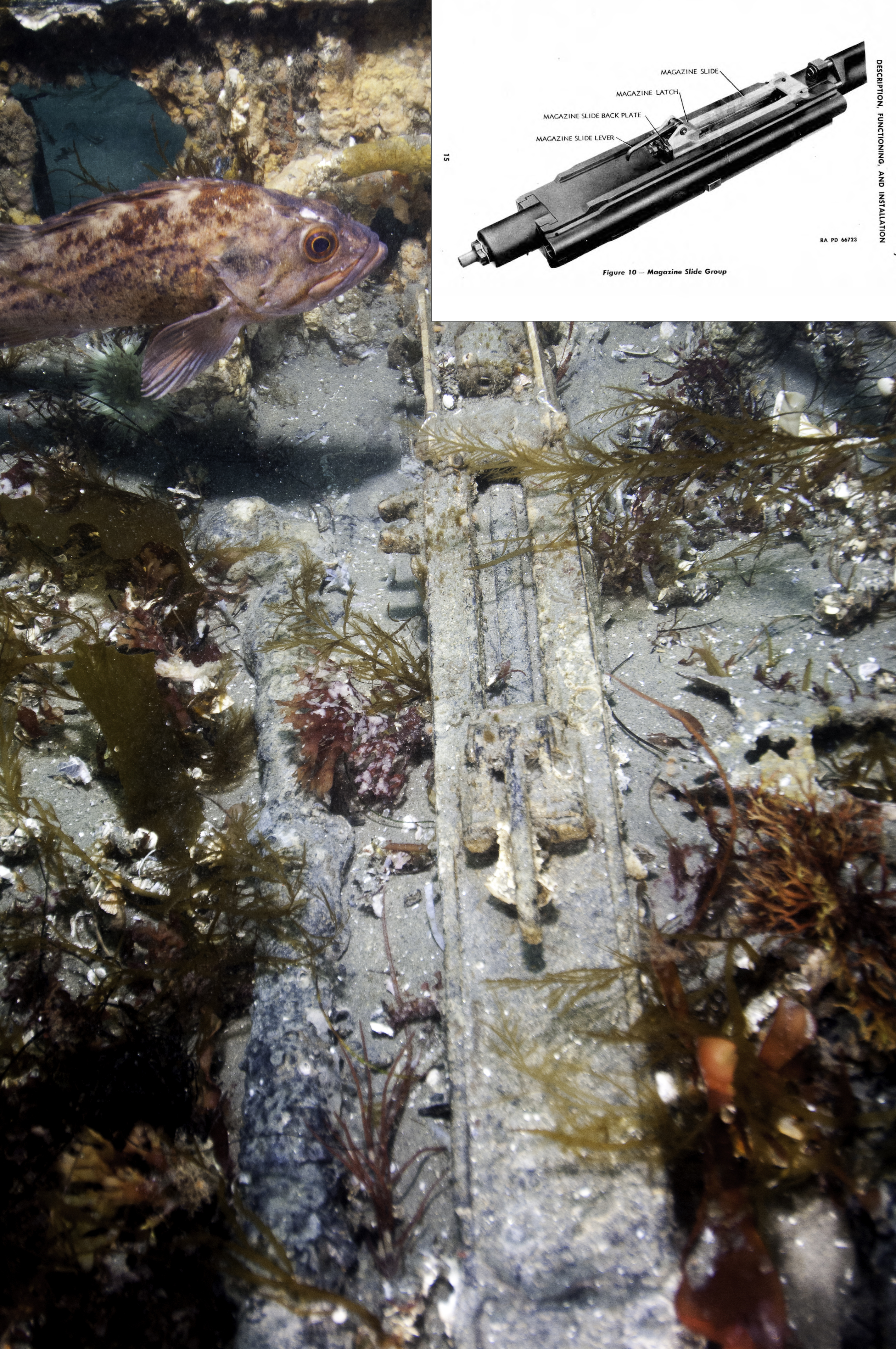

Initially, all we were certain of was that the aircraft had a single engine, an approximate wing span of 50′ and was obviously military due to its armaments. Our find had four cannons, two on each wing, with a bore just the size of my thumb. By going to our local aerospace museum and sticking my thumb into the barrels of several wing guns we determined that the plane’s armaments had a bore of 20mm. Online we found manuals for the 20mm Browning M-2 Cannon, Naval edition. By comparing the pictures in the manual with our photos from the wreckage we positively identified the plane’s armaments.

(Above, Right to Left, Breach of Port Cannon #1 with Inset of Cannon Manual, Curtiss-Wright Cyclone 3350 Nose Down and Breach of Port Cannon #2 with Manual Inset.)

We then turned our attention to the engine. I contacted online wreck hunter extraordinaire, Gary Fabian of UB-88 fame who guided us through identifying the engine. By carefully counting the exposed cylinder heads

and confirming that the engine had a double-row of cylinders, we narrowed down the possibilities immensely. Only one single propeller-driven aircraft of this size had an engine this large, the A-1 Skyraider.

Our early research revealed that A-1’s had only two 20mm cannons, one per wing. With further digging, we discovered that in 1951 the AD-4 Skyraider was introduced with four M-2 cannons, two on each wing. Despite this fairly conclusive evidence, we had been advised by military aircraft experts that, unless we found the official bureau of aeronautic identification plate on the craft we could never positively identify the plane.

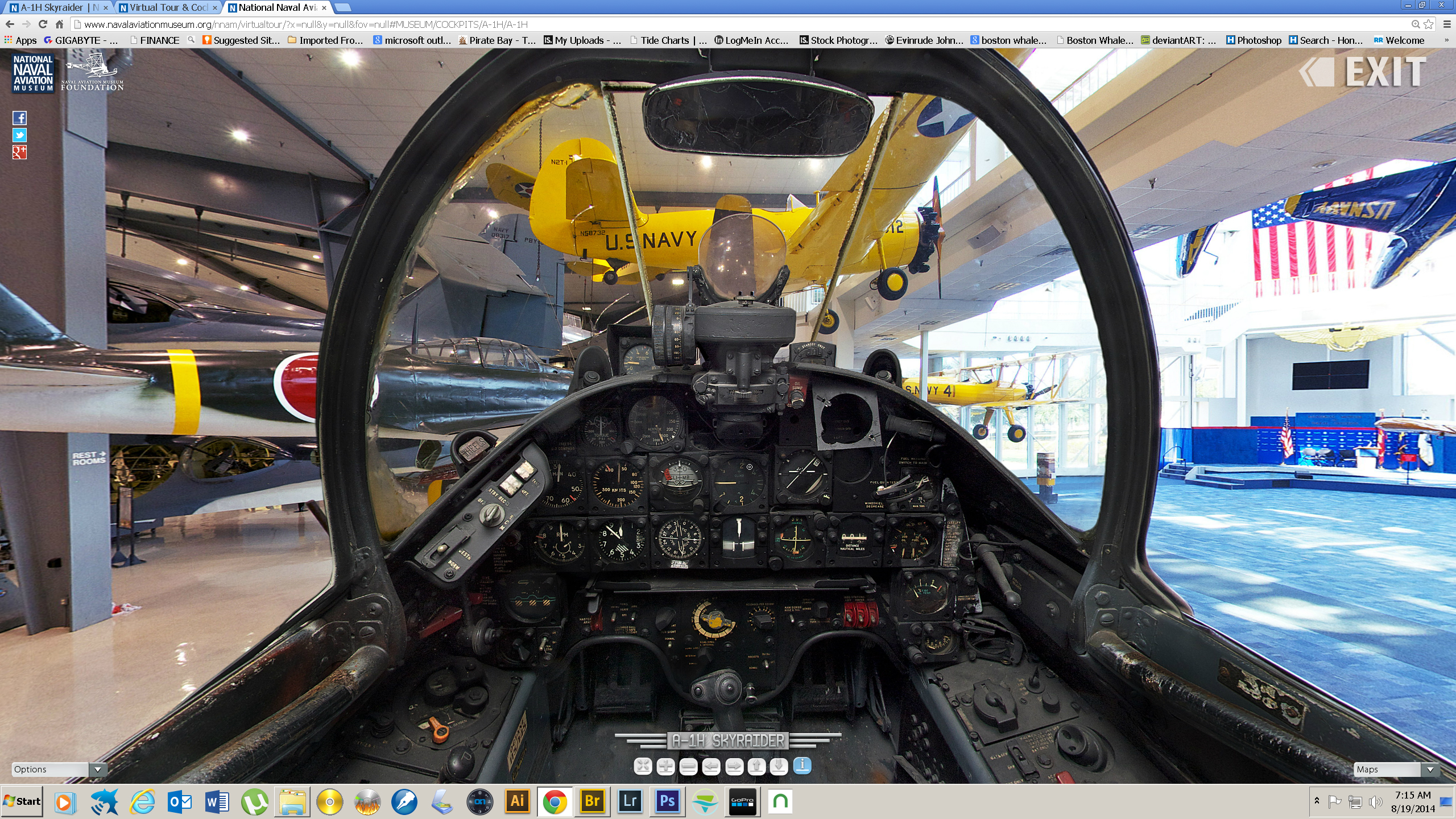

Once we had determined with some certainty that the wreckage was that of a Skyraider we utilized the Panoramic Virtual Cockpit page of the Naval Aircraft Museum in Florida’s website to determine the approximate location of the Bureau of Aeronautics Identification Plate. On our very next dive we were able to locate and photograph the identification plate.

The information from the plate positively identified the aircraft, but did not reveal how it ended up on the ocean floor. As indicated above, naval records exist as to almost all military aircraft. These records are available to the public and can easily be referenced once you have the serial number and the name of the manufacturer of the craft. By utilizing these records we were able to tell this story of the demise of a legendary warbird, forgotten but not lost.

Obtaining the information necessary to identify the aircraft was not without risks. Dozens of

dives on the site were necessary with cameras, measuring devices and other instruments necessary to record the wingspan, cannon dimensions and engine information. Most dives were in unfavorable conditions. Limited visibility, heavy surge and current, due to the shallow depth of the wreck site, were common and on one day in August a freak lightning storm passed over while we were gearing up.

By making videos of the wreck site and the use of email we were able to obtain the opinions of aviation experts as to the age and type of aircraft we had discovered prior to its positive identification.

Most of our dives were done using our 13′ yacht tender “Zig Zag.” Prior to our dives we did hours of sonar mapping using our Series 700 Humminbird Side Scanning Sonar. Reviewing the image data recorded on the sonar led to the aircraft’s discovery. By pure chance we made a timelapse video of our very first dive on the site in November 2013 before we even knew the wreckage was an aircraft.

What’s Next?

We have learned while investigating our find that most professional wreck hunters maintain a strict ethical practice of not publicizing the location of their discoveries in order to preserve the sites for as long as possible. Though we are by no means professional wreck hunters, we have chosen to adhere to that practice.

Legally the wreckage of any U.S. military aircraft is strictly protected by federal law. The aircraft, its artifacts and debris field may not be “disturbed” without severe civil and even criminal penalties pursuant to 14 U.S.C.A. §1401, 2004. (Click Code Section for full Statutory Reference with Highlights.)

Since the discovery, we have contacted several aviation history museums in an attempt to solicit preservation or recovery of the aircraft via a permit from the Navy. Until such effort bears fruit, the wreck will be left intact in its present position, awaiting discovery by other curious divers looking for a new dive spot and an exciting glimpse of aviation history.

Further information about this wreck site is available by emailing us at [email protected].

Links

Link to Article Written for the Diver Alert Network’s (DAN) Alert Diver Magazine, Winter 2015

http://www.alertdiver.com/hidden-in-plane-sight

February 12, 2015 Local News Coverage:

http://www.10news.com/news/wreckage-of-korean-war-era-plane-found-in-san-diego

http://www.cbs8.com/story/28099023/divers-find-warplane-that-crashed-six-decades-ago

http://fox5sandiego.com/2015/02/12/divers-discover-korean-war-plane-wreck-off-san-diego-coast/

http://www.kusi.com/clip/11188923/daves-world-of-wonder-lost-at-sea

Resources:

Law Offices of Dennis D. Burns, Sponsor

San Diego AIr and Space Museum

UB-88, Gary Fabian Website

National Naval Aviation Museum Website

Chuck Nicklin Website

Media and Reference:

Discovery Channel “Wings” Episode Featuring A-1 Skyraider

Humminbird Side Scan Sonar-Unofficial Forum

Records of the Bureau of Aeronautics

Restored A-1 Skyraider AD-4L Flying at Airshow Video